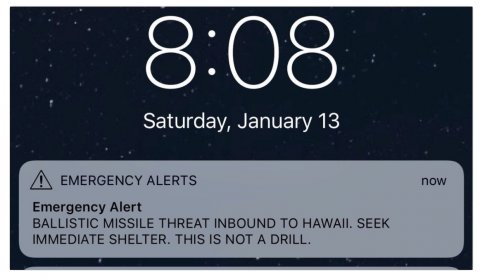

If you live in Hawaii, last weekend you experienced quite a scare… Maybe if you live anywhere. As many of you know there was a false alarm sent out through the emergency notification system that the state of Hawaii uses to warn residents of possible threats or emergencies.

What does that have to do with school, business or event safety? Surprisingly, a lot.

Truth be told, each organization we work with has (or should have) an emergency notification system. Our work emanates from protecting a community and in a world where surprises are ubiquitous and the only way to enact immediate action from your community (whether it be ‘get out!’, ‘run, hide, fight’, or any other message), is to leverage an emergency notification system.

One of our school communication directors has a cell phone case that I think says everything about emergency messaging (maybe all messaging). It simply reads: “You should dance like nobody's watching, but you should email like the entire world can see”.

All emergency notification systems should be designed to communicate to the entire community. That should include staff, faculty, students, parents, Board of Trustees members, friends of the school, and many, many others. My challenge to you is to install three basic rules for your emergency notification system:

Rule 1: Always have a “proofer.” Somebody should proofread your message even in the most emergent of situations and even when you're using a template. Frankly it doesn't need to be a communications expert, it just needs to be somebody who can use common sense and spot any errors that you as the sender may have inadvertently created.

Rule 2: Always test your message by reading it aloud. Typed messages often include grammatical and spelling errors that you can quickly and easily recognize when reading aloud. Reading it out loud also forces you to slow down a bit and when you’re in crisis, that can be helpful - catch your breath, read your message aloud and listen to how it sounds. Then, hit send.

Rule 3: Don’t let the first time you send a message be in a crisis. Practice builds confidence. Use practice during table-tops, drills and other activities to ensure that you know how to send a message. Use that practice to create and build templates. Use the practice to make sure you and at least 3 other people know how to hit send during a crisis.

We’re not saying anything about Hawaii’s incident in this message. We don’t fully know what happened there. That said, we do know that similar mistakes can happen to you and therefore, we want you to use this incident as a catalyst to your own preparedness.

Safety starts with confidence - and confidence comes from experience. Click the button below to schedule some time with our experienced school safety consultants.

And, subscribe to our blog below!